Project Bread’s Community Power Fund Empowers Grassroots Leaders to Make Hunger History

Olivia Deng

When Stacey Borden, Founder and Executive Director of New Beginnings Reentry Services, Inc. (NBRS), tells Erica’s story, she lights up. Once defined by a conviction, Erica refused to let her past dictate her future. With courage and determination, she transformed her life, enrolling in the New England Culinary Arts Training (NECA) program, later joining their staff, and even completing a business entrepreneurship course at Boston College. Her journey came full circle when she created her own line of seasonings, a symbol of flavor, freedom, and newfound purpose. “It was phenomenal,” Borden said. “She developed her own seasoning, which said, wow, we could have a formerly incarcerated woman have some passion and find her leadership, find her niche in the world."

Erica asked Stacey about teaching culinary at NBRS. They signed a contract, and now she’s helping formerly incarcerated folks learn cooking skills. “[It] is incredible that someone in the last two years can enlighten themselves and be that passionate about food and help formerly incarcerated people learn not only employment for career development, but understand culturally how food and seasoning, just how to cut food and develop seasoning.”

Borden is a formerly incarcerated woman herself who was inspired to start NBRS due to the injustices she experienced with herself, her community, and her family. And now, thanks to Project Bread’s Community Power Grant, she’s partnering with Roslindale Food Collective to lead an innovative, community-driven initiative that links food justice with reentry support and rebuilding of community strength.

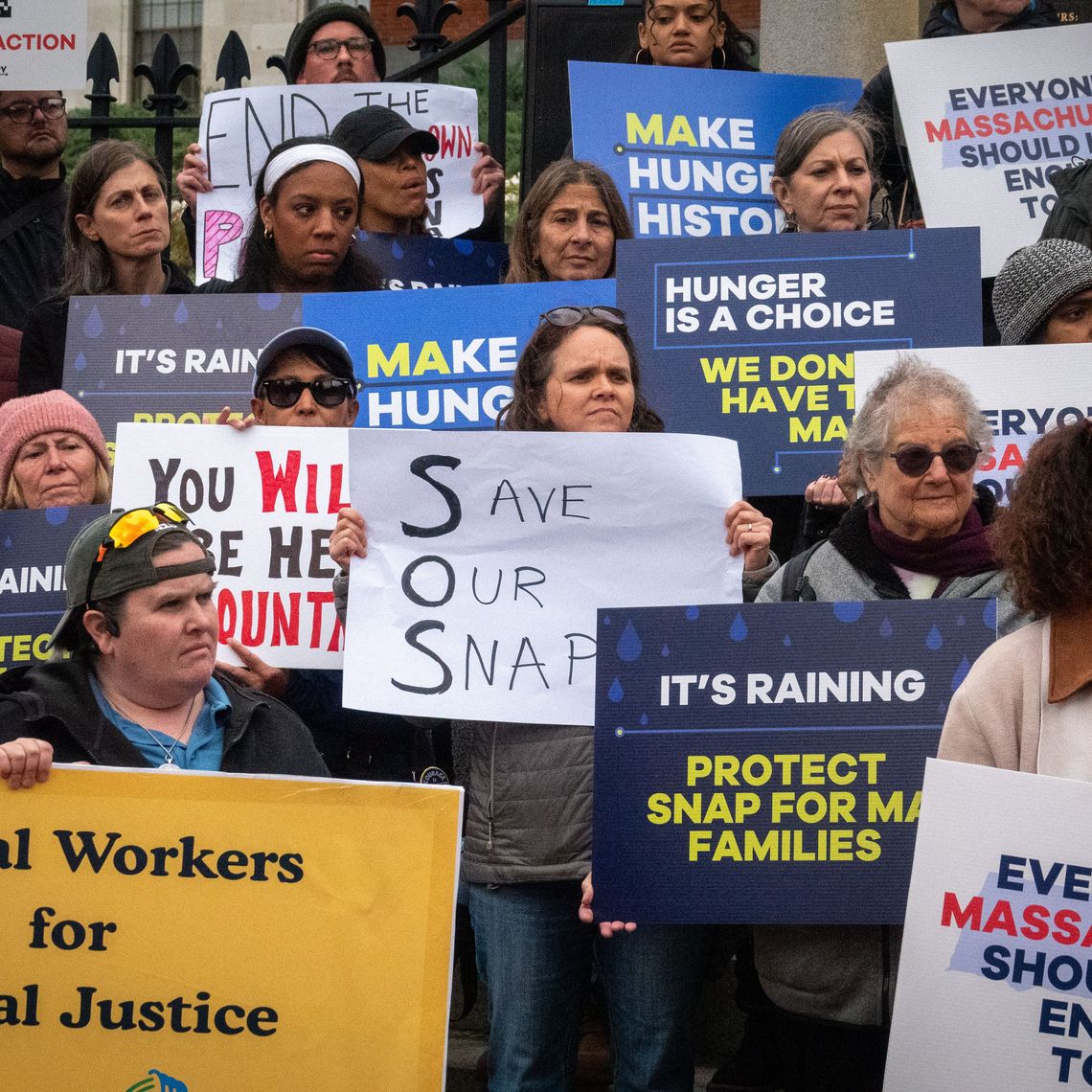

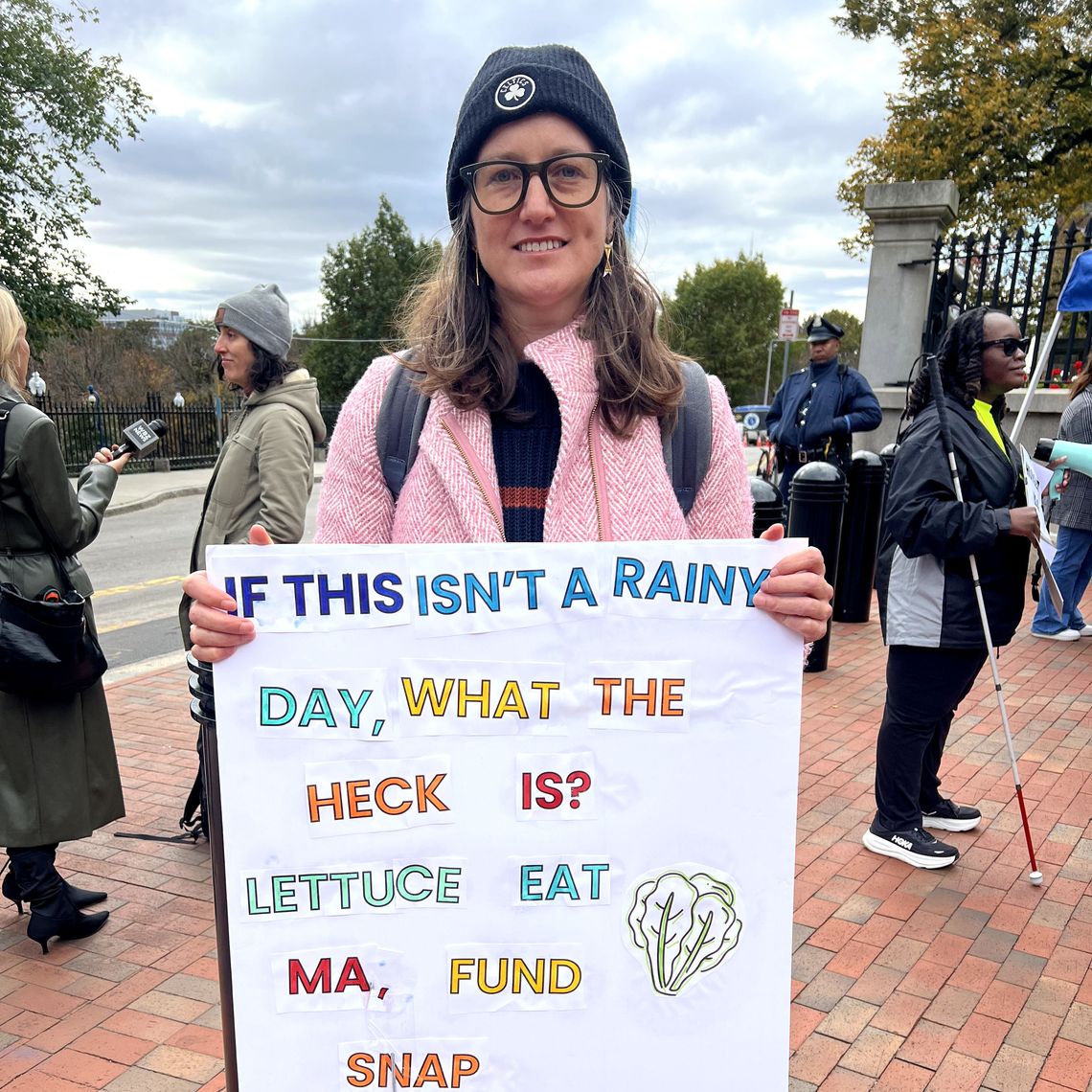

Across Massachusetts, local leaders are redefining what food justice means. From training Arabic-speaking immigrants in Revere to empowering seniors as advocates in MetroWest, five organizations are redefining the fight against hunger through Project Bread’s Community Power Fund, part of the Make Hunger History initiative.

The inaugural Community Power Grants invest a total of $97,000 in grassroots organizations that tackle the root causes of food insecurity, rather than just its symptoms. Each grantee is working to shift power directly into the hands of those most affected by hunger while advancing one of the five pillars of change guiding the work of Make Hunger History (MMH):

-

Revere Arabic Community (RAC) - MHH Pillar: Root Causes

-

Boston Food Access Council (BFAC) - MHH Pillar: Food Access

-

Roslindale Food Collective + New Beginnings Reentry Services - MHH Pillar: Priority Communities and Populations

-

MetroWest Food Collaborative (MWFC) - MHH Pillar: Food Access

-

Hampshire County Food Policy Council (HCFPC) - MHH Pillar: Root Causes

“Our mission is to build a movement to permanently end hunger in Massachusetts. In order to do this, we know that we need to bring together a diverse coalition of advocates, policymakers, businesses, individuals with lived expertise, and community members to collaborate, advocate, to mobilize our communities toward ending hunger for everyone in our state — forever,” said Spencer Masterson, Director of Make Hunger History at Project Bread. “The Community Power Grant ensures that grantees’ community leadership, lived experience, and organizing efforts are directly connected to this statewide movement.

Masterson explains that the Community Power Fund emerged from a desire to rebalance the distribution of power in anti-hunger work. “We know that for many advocates and service providers, finding the time and funding to be engaged in coalition and advocacy work can be challenging. The Community Power Fund seeks to eliminate some of the barriers to participation, while also supporting community-driven efforts to build power in local communities that will also support statewide efforts.”

MetroWest Food Collaborative: Empowering Senior Advocates

For Callie Coughlan, coordinator of the MetroWest Food Collaborative, the fight against hunger begins with those who have experienced it firsthand. With two decades of experience in nonprofit and municipal work, Coughlan said her passion for food justice began when she joined the Worcester County Food Bank.

“I think really [that’s when] I found my passion… for food insecurity and just ensuring that folks have access to the food that they need,” she said. “I just feel like it's a human right that everybody should have access to the food that they need.”

Boston Food Access Council: Strengthening Grassroots Leadership

In Boston, the Boston Food Access Council (BFAC) is working to ensure that the people most affected by hunger help shape the solutions. Steering committee member Seana Weaver, who has spent years in food justice roles, said the coalition’s goal is to bring residents, advocates, and policymakers into the same conversation.

“We are a community-led coalition,” she said. “We work to empower Bostonians with the knowledge to [access] food access resources, and to bring together and amplify community voices, needs through collaboration, partnership, advocacy, and awareness building.”

BFAC’s strength, Weaver said, lies in its deep connections with city leaders and residents alike. “We have connections with city council members, the Office of Food Justice, and other policymakers and legislators,” she explained. “We contact them and make sure that they're up to date on what the coalition is looking for and what the conversation is… in order to support advocacy work.”

With support from the Community Power Fund, BFAC is taking two major steps forward: bringing in professional leadership and developing a paid network of community advocates. The organization is using the grant funding for two main purposes. First, they plan to hire a part-time executive-level leader, referred to as a fractional executive director. Second, a portion of the funds will support community outreach efforts, including promoting SNAP benefits and improving access to food resources.

These advocates, she added, will be trained and compensated for sharing vital information about benefits programs, such as SNAP and HIP, at farmers' markets, community events, and other food access points. “That would be people who are directly in the community being paid dollars to do their work and to be trained to do outreach,” Weaver said.

She emphasized that the advocates will bring critical lived expertise. “We’re looking for people who have experience with or are currently experiencing food insecurity, people who have a story to tell and want to tell that story,” she said.

Ultimately, Weaver hopes the program will strengthen Boston’s food justice network while amplifying residents’ voices. “What I really hope is for both the steering committee members of the coalition and people who are witnesses… to get to witness work that is actively moving the needle on food justice and food access in Boston,” she said.

Roslindale Food Collective & New Beginnings Reentry Services: Healing and Advocacy Through Food

When Leah Arteaga, founder of the Roslindale Food Collective, first began rescuing food from a Whole Foods in Beverly, she had no idea she was building the foundation for a movement. She started small, setting rescued groceries on her picnic table and inviting neighbors to take what they needed.

“I would go every Saturday to pick up the food at Beverly Whole Foods and bring it back and put it on my picnic table,” she recalls. “I would invite people from the community to come and get it. And I was like, okay, 20 people are getting food. That’s cool.”

From that simple act, a grassroots network began to grow. When a neighbor offered to help, Arteaga turned the effort into a fully fledged volunteer program, organizing weekly distributions and coordinating with local donors. “We then started to bring in more food and more food,” she said. “And during the pandemic, we were making upwards of 160 boxes. We had primarily immigrants coming to our program that was operating out of a parking lot in the back of a middle school.”

The model was built on trust, dignity, and mutual aid. “Every volunteer can pack a bag for themselves,” Arteaga explains. “It turns it into, instead of community service, which is, ‘I’m serving someone who’s below me,’ it’s mutual aid: my family has a need and I’m helping your family that has a need, and we are on the same level.”

"It’s mutual aid: my family has a need and I’m helping your family that has a need, and we are on the same level." - Leah Arteaga

Her own experience of suddenly facing food insecurity as a single mother deepened her empathy and her resolve. “I got turned away at a food pantry ’cause I was missing one of my kids’ social security cards,” she recalls. “Here I am, like this educated woman who feels like I have dignity, and now I’m stripped of that dignity because I can’t even get food because of a technicality.”

That moment crystallized what she wanted her organization to be: a place where everyone is welcomed and treated with respect. “To me, addressing food insecurity with dignity means that you are allowing people to come to your program without asking any invasive questions,” she said. “You don't ask how much they make, how many children they have, where they live. Their zip code has nothing to do with the fact that they need food.”

Now, through the Community Power Fund, Arteaga has joined forces with Borden to create a groundbreaking collaboration that connects food justice with reentry support for formerly incarcerated people.

“We have an adult reentry day center. We service all genders through the world of arts and healing, through psychodrama therapy, through counseling for drug abuse or alcoholism, through trauma. Bottom line is we service the whole self holistically,” Borden said.

When Arteaga approached Borden about applying for the Community Power Fund together, the partnership felt natural. “I fell in love the minute I met Stacey,” Arteaga said. “What we’re doing collaboratively between New Beginnings and Roslindale Food Collective is something that neither of us could have done on our own.”

Their project will host a four-part community series that blends storytelling, shared meals, and cultural celebration, an extension of New Beginnings’ trauma-informed arts programming and the Food Collective’s community-based food access model. “We already have events that show how our formerly incarcerated people heal through the world of arts,” Borden explains. “This is an extension of that, healing through food.”

The series will culminate in a Community Food Justice Manifesto, co-created with residents who have been impacted by incarceration and food insecurity. Each event will feature culturally significant meals, including Cape Verdean, Haitian, African, and American cuisine, prepared and shared by local chefs, many of whom are formerly incarcerated.

“What we are doing here is really giving them a surprise, an awakening, some love,” Borden said. “People that have been in prison don't get nutritional food… you might not get to eat if you're talking in line. They have no fruit. What we are doing here is really giving them something different, a different taste, a different culture of what food can be.”

For Borden, this work centers on rebuilding identity and community after incarceration. “We’re creating a manifesto,” she said. “What we hope to get out of it is building a stronger community of leaders that know that they're loved and cared for and joyous freedom to be expressive.”

The partnership is also about community power. As Arteaga puts it: “It’s going from we and them to us, which is just a beautiful concept.”

Borden agrees. “If you think about the Last Supper and how they all came together at the table, that was community,” she said.

Hampshire County Food Policy Council: Organizing for Systems Change

In Western Massachusetts, the Hampshire County Food Policy Council (HCFPC) is proving that lasting food justice starts with community voice. Council coordinator Kristen Whitmore and member Kia Aoki said the group formed at the height of the pandemic, when neighbors banded together to ensure no one went hungry.

“I live in public housing,” Aoki said. “In the very beginning of the pandemic, we were all trying to figure out how we can help each other and make sure that we all have enough to eat in our community. And that kind of coincided with the beginning of the Hampshire County Food Policy Council.”

The council now operates using a collective decision-making model called sociocracy. “We use a model called sociocracy, which has to do with the way that our organizational structure works as well as the way we make decisions,” Whitmore said. “We’ve done a lot of story collection… and we have a community story archive on our website.”

For Whitmore, who grew up in a family of farmers, food justice is deeply personal. “Realizing that people's access to food or access to land is not equitably distributed and that some people don't know where their food comes from or that it can be really hard for people to even access fresh food was like a big signal to me that this is something we need to work on,” she said.

Aoki’s perspective comes from lived experience. After losing housing, she saw how systemic barriers keep families trapped. “I suddenly became homeless with two young kids,” she said. “And landed in a system that doesn't let you back out. I began to understand and see...how difficult it was to maintain access to really good, healthy food and what it means to not have enough money to afford the basics.”

Together, Whitmore and Aoki envision a model where policy, storytelling, and lived experience combine to shape fairer systems for everyone.

“I began to understand and see...how difficult it was to maintain access to really good, healthy food and what it means to not have enough money to afford the basics.”

Kia Aoki, co-founder of the Hampshire County Food Policy Council

Revere Arabic Community

The Revere Arabic Community (RAC) is creating a platform for immigrant-led policy change in Revere. Through Project Bread’s Community Power Fund, RAC will enhance its Immigrant Family Support and Food Distribution Program to better meet the needs of immigrant families in Revere. The project focuses on building immigrant leadership, improving access to food, and creating long-term community solutions.

“These activities help families learn about available food programs, build confidence in speaking up for their needs, and strengthen partnerships between community groups and local agencies,” Aboufouda said. Over time, RAC aims to form a permanent immigrant-led advisory group that will continue advocating for culturally inclusive food programs and policies that reduce food insecurity across Massachusetts.

Aboufouda emphasizes the broader impact of the work: immigrant families not only receive food today but also have the power to shape a more equitable food system for the future. For RAC, sustainable community power means that the people most affected by hunger are empowering immigrant families to advocate for themselves, make decisions that affect their community, and shape policies that reflect their needs and values.”

Through leadership development, culturally responsive programming, and advocacy training, RAC is helping ensure that immigrant voices are central to Massachusetts’ food justice movement and that families have the tools and confidence to create lasting change.

Building the Power to End Hunger

Each of the five grantees is demonstrating that when communities lead, systems can be transformed. Together, they are building the foundation for a Massachusetts where everyone has reliable access to nutritious, culturally relevant food and the power to shape the future of food security.

Through the collective power of Make Hunger History, Project Bread is investing resources to build the foundation for a food-secure future where no one has to worry where their next meal is coming from.