Boosting SNAP Benefits to Feed Massachusetts Families

Project Bread

Everyone should have access to the food they need to live a healthy lifestyle. A recent increase in benefits works to bring that reality into existence.

On October 1st, 2021, the now 990,548 Massachusetts residents receiving Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits began to receive a small, but significant increase in the amount of funds they have available to pay for groceries. On average benefits increased by $36.24 per person, per month due to a United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) recalculation and modernization of the Thrifty Food Plan, used to calculate benefit amounts. Project Bread applauded and continues to celebrate this decision to provide a permanent 21% increase to SNAP, which is the largest increase in the program’s history. While this increase is indeed cause for celebration, Project Bread also encourages legislators to continue to seek ways to improve access, expand eligibility, and further increase the benefit amounts of SNAP.

SNAP provides households with an electronic benefits transfer (EBT) card that can be used at nearly 5,000 retailers across the state such as grocery stores, convenient stores, farm stands, and recently even a handful of online grocery stores. This provides recipients the dignity of choice in how, where, and what groceries they purchase to fit their lifestyle, cultural heritage, and diet. SNAP is the largest, and most important anti-hunger program in Massachusetts, currently serving 1 in 7 residents of the Commonwealth. While the emergency food system provides an invaluable service, for every 1 meal served by food pantries, community meal programs, and food banks, SNAP provides 9. Furthermore, SNAP lifted an average of 133,000 people out of poverty, including 46,000 children in Massachusetts each year between 2013 and 2017.

A recent senior caller to the FoodSource Hotline from Monson, MA learned from our team that he would qualify for SNAP benefits of about $145 per month based on his income and expenses information. He had had no idea that he could expand his tight budget through SNAP and purchase the food he needs until he received our postcard promoting the program. For this caller and many others, these benefits are an incredible and necessary lifeline.

The Thrifty Food Plan

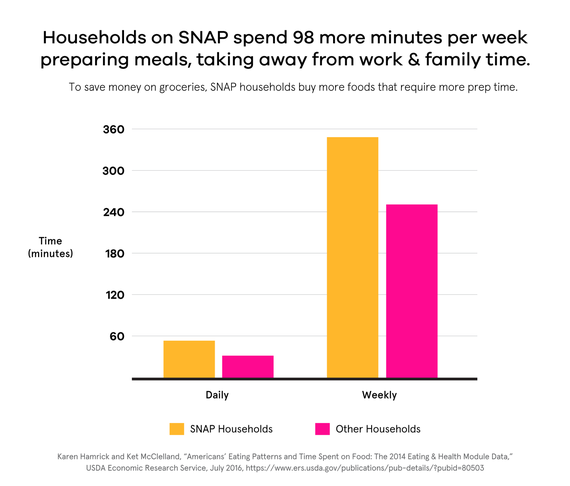

The Thrifty Food Plan was designed by the USDA to calculate the most minimal amount a household can spend to achieve a nutritionally adequate diet. Originally called the Economy Food Plan in 1962, it was revised and renamed the Thrifty Food Plan in 1975. For the next 45 years, the Thrifty Food Plan stayed cost neutral except for monthly adjustments based on the cost of food, with SNAP benefits only increasing once per year. The changing ways people purchased, prepared, and consumed food, as well as dietary science was not taken into consideration until now. One example of the outdated nature of the Thrifty Food Plan was the assumption that households with low-incomes would spend 138 minutes per day preparing meals at home using scratch ingredients such as dried beans versus convenience products such as canned beans. The USDA’s research found actual SNAP households spend an average 50 minutes per day and non-SNAP households only spend 36 minutes per day.

In the 2018 Farm Bill, the U.S. congress directed USDA to reevaluate the Thrifty Food Plan based on current food prices, food composition data, consumption patterns, and dietary guidance by 2022. With the increasing attention on food insecurity during the COVID-19 pandemic, President Biden signed an executive order during his first week in office directing USDA to expedite this process.

SNAP benefits were not and will not be enough to cover household needs.

As critical as SNAP is for households who receive it, benefits were not enough for most of Massachusetts families. Most households run out of their benefits before the end of the month. The USDA’s own research found that by the middle of the month, SNAP households had used more than three-fourths of their benefits. Additionally, the Urban Institute used available data from the US Census Bureau to analyze food spending among low-income households finding that SNAP just was not enough for the majority of families in the majority of counties. Compared to the maximum SNAP benefit per meal, the pre-pandemic benefit did not cover the cost of a low-income meal in 96% of counties in the United States including all of the counties in Massachusetts. Nationally, the Urban Institute found that the average cost of a meal in 2020 was 22% higher than maximum SNAP benefits, higher than the recent benefits increase included above as well.

In December 2020 and extended until September 2021, households receiving SNAP received an additional 15% in benefits. Even with boosted benefits, SNAP was insufficient in 41% of counties. As a higher cost of living state, the average cost of a meal still outpaces these boosted SNAP benefits in all, but one Massachusetts counties.

In its annual report on food security in the United States, the USDA looked at food spending by food secure and food insecure households. The data shows that households identified as food secure spent, on average, $209 for a family of 4 weekly or 135% of the Thrifty Food Plan. In contrast, households identified as food insecure reported spending $177 for a family of 4 weekly or 114% of the Thrifty Food Plan. In short, food insecure households, on average, spent more than they received in SNAP benefits on food, supplementing from an already limited household budget, but still less than what is needed to be food secure.

By all these measures a 21% increase is insufficient for Massachusetts residents, and the average food insecure households would still be required to use additional resources, reduce meal sizes, or skip meals altogether in order to make their food dollars last. The chart below illustrates the gap between SNAP benefits and the average meal under different scenarios. Currently, households who would normally receive the maximum in SNAP benefits pre-pandemic receive an additional $95 per month. With this additional amount, current benefits are the closest they have ever been to being sufficient. However, this boost, called emergency allotments, are set to expire when there is no federal and state public health emergency, so it is possible we will return to “normal” sometime in 2022 resulting in a benefit cliff for food insecure families.

We are currently the closest we’ve ever been to benefit adequacy, with the average households in Hampden and Bristol Counties theoretically having enough to spend on food when receiving the maximum amount of SNAP. It’s important to note, though, this is using 2020 data on food costs, which have risen with inflation. When emergency allotments end, households receiving SNAP benefits will still fall short each meal by an average 14 cents or more per person. In Barnstable County, this shortfall between what a meal costs and what can be afforded using the maximum SNAP benefit will grow to nearly a full dollar ($0.97).

This is all based the cost of food in 2020, but we know low-income households have limited resources when a crisis hits, supply chain problems limit availability of products, or inflation increases the cost of food—all things that have happened over the last year. Going above what is deemed as minimally necessary helps families maintain access to a healthy diet even in particularly turbulent times.

We often hear from callers on our FoodSource Hotline that benefits are simply not enough. One major group that struggles affording groceries with SNAP are people with dietary needs for religious or medical reasons. One recent caller shared with us her challenges managing celiac disease and avoid gluten on a tight budget.

Just this month, a senior caller from Revere, MA referred to us by his health center shared, “I have SNAP, but I usually run out toward the end of the month - like now I have none left." Our Hotline counselor provided information on food pantries in the area to try to fill the gap. "I try to buy fresh food for my health, but everything has been so expensive lately."

While SNAP eligibility needs to be expanded, there are many individuals and households who do not quality for the many programs beyond SNAP. For example, one man from Taunton who was unemployed largely because of a personal health emergency in 2021. He didn’t have enough work history to receive unemployment so while his $250 per month in SNAP was a big help, it simply was not enough. The October 2021 increase and emergency allotments have helped people like him, but a larger permanent increase is still needed to ensure they have access to healthy and sufficient food.

Where do we go from here?

Recalculate SNAP benefits based on the Low-Cost Food Plan: In 2017, U.S. Congresswoman Alma Adams introduced the Close the Meal Gap Act which in addition to other important reforms would shift SNAP benefits to be calculated with another USDA Food Plan: the Low Cost-Food Plan. The Low-Cost Food Plan would represent an approximately 30% increase to benefits over the old Thrifty Food Plan. Included on the chart above, the Low-Cost Food Plan would bring us even closer to benefit adequacy.

Make the Healthy Incentives Program permanent: Launched in 2017 statewide, HIP provides a dollar-for-dollar match, up to a monthly limit based on household size, for SNAP dollars spent on fruits and vegetables purchased at farmers markets, farm stands, mobile markets, and community support agriculture programs across the state. HIP supplements inadequate SNAP benefits while increasing access to healthy, local food. HIP has only existed as part of the state budget, we need to pass legislation to make HIP permanent!